MODULE 12 - TRACKING & BLOOD-TRAILING

CHAPTER 1: THE ANATOMY OF AN ELK

Elk are big, tough animals. Even with a well-executed shot, tracking can be a vital skill to ensure recovery of the animal. Understanding the anatomy of the elk will help you analyze what kind of a hit you have, and help determine what kind of a tracking job lies ahead.

Obviously, our main goal when hunting is to get an arrow or a bullet solidly into the vitals of the elk. Rifle hunters often have a larger margin for error, as the shock caused by high-powered elk rifles can drop an elk in their tracks, sometimes even if that shot is outside the normal “kill zone” (i.e., think neck shots or shoulder shots). An arrow in the neck or the shoulder of an elk, however, is not usually going to bring fatal results.

THE VITALS

The body cavity of an elk can be broken down into two segments – the thoracic cavity (in front of the diaphragm), and the abdominal cavity (behind the diaphragm). The diaphragm is simply a sheet of muscle that separates the two cavities.

The front cavity (thoracic) contains the “vitals” of the elk – the heart and lungs – as well as several arteries that supply blood to and from the heart from the rest of the body. This is where you want an arrow or bullet to hit for a fast, clean kill. The back cavity (abdominal) contains the stomach and intestines, and is commonly referred to as the “guts”. An arrow or bullet in this area will almost always result in fatality, but the death can be slow and the bloodtrail can be minimal, making the chances of recovery far lower.

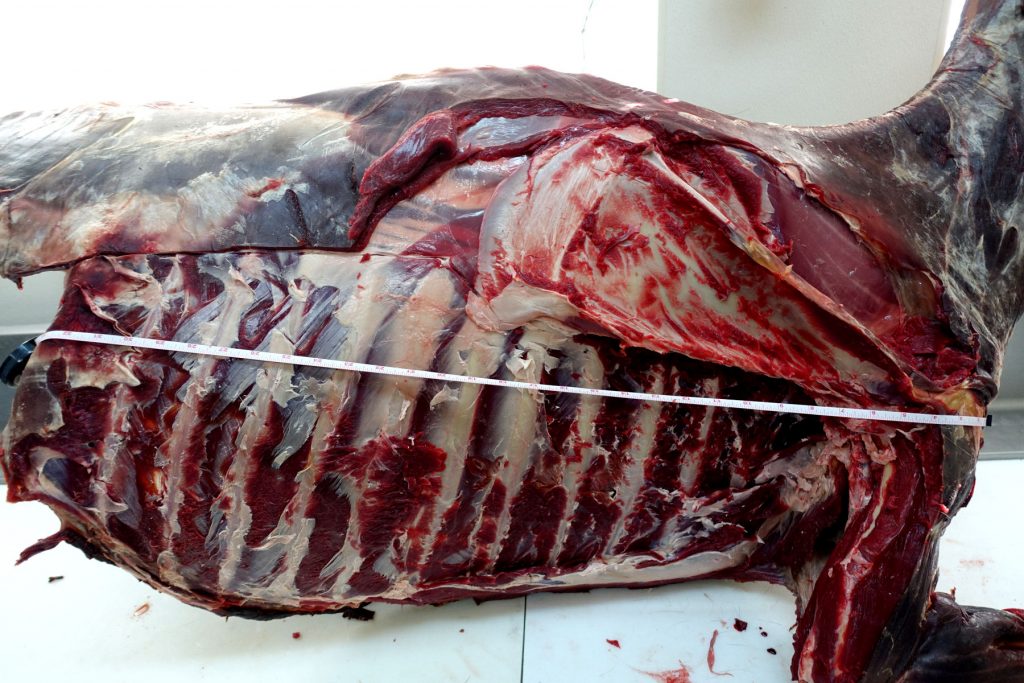

To help illustrate this discussion, I spent a day at a wild game processor, completely dissecting an elk carcass. Actual measurements, weights, and images were taken to provide factual representations of the anatomy of an elk.

THE THORACIC CAVITY

The thoracic cavity (vitals) of an elk is housed inside the protective structure of the rib cage. Additionally, the front portion of the vitals are also protected by a large leg bone and scapula (shoulder blade) on each side of the elk. Looking at an elk from the broadside view, the heart is tucked just above the front leg bone, and sits in the middle of the lower 1/3 of the thoracic cavity. The lungs extend from the rear edge of the diaphragm forward to just in front of the leg bone and shoulder blade. A bullet from a rifle or an arrow from a bow typically has no problem penetrating through the hide and the rib bones to get inside the thoracic cavity. However, an arrow will typically not penetrate through the leg bone or thicker parts of the shoulder blade, so understanding where the bone structure lies is definitely important. Typically, an arrow placed inside the thoracic cavity will provide fatal results, but there are a few locations within this area to keep in mind.

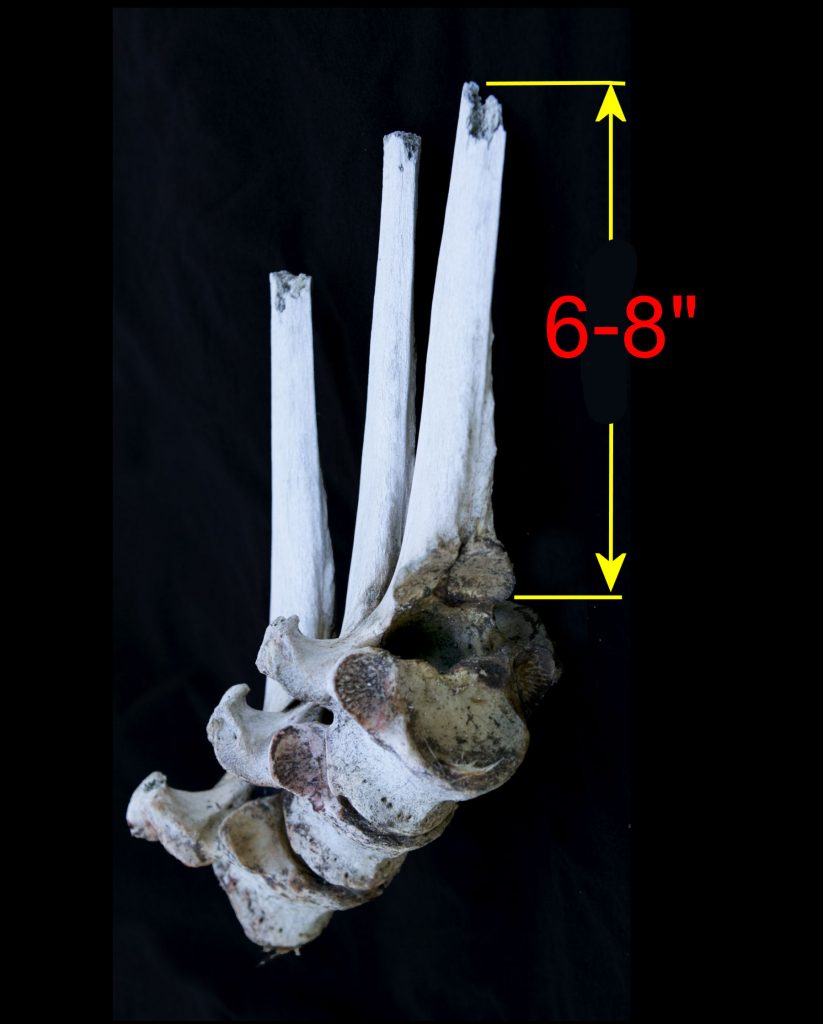

First, there is an area high in the thoracic cavity where it is possible to slide an arrow through without getting inside the thoracic cavity. Many hunters refer to this as the “void”, and while it often times looks like a solid hit, it is possible to miss the vitals completely. This is due to the structure of the vertebrae in this area.

The actual spinal cord of an elk is housed within the vertebral foramen of the “backbone”. This is the main opening in the vertebrae. In the area above the thoracic cavity, this opening where the spinal cord lies is actually located around 6” below the top of the elk – not right at the top of the back as you might think. The area above the vertebral foramen/spinal cord is made up of bones that extend upward off the vertebrae, known as the spinous process. There are no vitals in this area. If you hit within 6” or so from the top of the back on an elk, you will not hit any vitals whatsoever. A shot in this area, can be enough to knock an elk down, but it won’t usually keep it down or be fatal. It is also possible to slide a bullet or an arrow between spinous processes and get nothing more than a simple flesh wound and no blood.

Another consideration when talking about the thoracic cavity is that the lungs do not completely fill up the inside of the rib cage. There are areas in front of the diaphragm within the rib cage where an arrow or bullet can slide through and actually miss the vitals. The area just under the vertebrae in the very top portion of the thoracic cavity is supported and protected by a layer of muscle. This provides a small buffer between the top of the lungs and the bottom of the vertebrae. A bullet or an arrow anywhere within 9” or so from the top of the back can slide through without fatal effects. Within this area, the only thing that really has a chance of bringing an elk down is a direct hit to the vertebrae/spinal cord. Anywhere else within this region will likely result in nothing more than a mere flesh wound.

Within the thoracic cavity, one of the largest protective obstacles that archery hunters need to consider is the scapula (shoulder blade). A good portion of the top part of the lungs is actually covered by the shoulder blade. However, it is relatively thin in this area, and a well-tuned arrow shot out of a bow with enough kinetic energy can pass through the scapula. If you are shooting a bow with lower poundage or too light of an arrow, however, the shoulder blade can cause enough resistance to not penetrate or to only penetrate enough to catch one lung. Regardless of bow/arrow setup, an archery hunter will want to recognize where the scapula lies so they can avoid hitting it.

Another area that can provide a great “looking” hit but a long tracking job is the area right behind the heart. In fact, a shot in this area can leave you feeling like you hit exactly where you were aiming, yet not recover the elk. Due to the layout of the vital organs, it is possible to hit right behind the heart, yet only catch one lung or actually miss the lungs completely.

Directly underneath the thoracic cavity is a section of muscle known as the brisket. A low shot in this area will generally produce a large amount of “muscle blood” initially, but the bloodtrail will often become non-existent after only a few hundred yards. Although the initial bloodtrail will lead you to believe that you should find the elk lying dead just ahead, the blood loss is usually not enough to be fatal.

THE ABDOMINAL CAVITY

Behind the thoracic cavity lies the abdominal cavity – the intestines, the stomach, the guts. A shot in the abdominal cavity typically produces a long, difficult tracking job. It will typically be fatal, but the bloodtrail can be minimal and the amount of time needed for the elk to expire can be several hours, even days. There is a large amount of protective fat and tissue surrounding the abdominal cavity, which can act as a seal to keep blood from being exposed externally. This can mean little or no blood to follow.

I have personally seen an elk that was shot in the abdominal cavity still on its feet and moving a full 36 hours after the shot. Persistence and patience led to the recovery of that elk just a few hours later, but there were fewer than 10 drops of blood to follow during the final 8 hours of tracking. Again, a shot in this area will almost always end in death, but an elk can stay on its feet and cover a lot of country – especially if bumped soon after the shot – when hit in this area. With minimal or no blood, this can often lead to a failed recovery of that elk.

NECK & LEGS

There are two additional areas that are external to the thoracic and abdominal cavities that are important to understand when it comes to the anatomy of an elk. The first area is the appendages – the front and rear legs. The second area is the neck.

A shot in the front leg structure (shoulder blade, humerus, radius) of an elk is typically non-fatal. Archery hunters definitely want to avoid hitting in this area. With a rifle, the shock from a shot to this area, combined with the resulting damage to the adjacent vitals, is typically enough to put the elk down for good. At the least, it will usually result in a broken front leg/shoulder which can drop the elk and provide an opportunity for a follow up shot if needed.

The upper portion of the back leg contains a large amount of muscle. A shot in this area will typically produce a decent amount of muscle blood, but without getting into the abdominal cavity, the chances of recovery are very low – with one exception. The femoral artery runs from the backbone down along the inside of the back legs. If you happen to get lucky enough to severe the femoral artery, the tracking job will typically be very short. This is not a shot you would ever want to aim for, but I have seen things go really bad in a shot and turn out really good thanks to the femoral artery.

The last area to understand in an elk’s anatomy is the neck. Rifle hunters will often aim for a neck shot to avoid the potential meat loss that can occur from a shoulder/thoracic cavity shot. The shock from a 180-grain bullet hitting solidly in the neck can be enough to drop an elk in its tracks. However, the primary source of fatality for archery hunters is sever blood loss, and the neck is not a good bet for achieving this.

It is worth noting, though, that the carotid arteries and the jugular veins run from the heart up along the spine through the neck. The carotid arteries are responsible for providing blood to the neck and head (brain) of the elk, and the jugular veins circulate the blood back to the heart. The severing of these arteries and veins will produce massive blood loss and quick death. Hitting these circulatory pathways from a broadside shot would be incredibly challenging, so it is not ever a good shot to aim for. However, this information will come in handy as we discuss shot angles, particularly the frontal shot, in the next section.

SHOT ANGLES

With an understanding of the elk’s anatomy, you can start to see where a bullet or arrow needs to hit in order to produce the best results. You can also see that there are areas within the standard vital cavities that might just miss the vitals. It’s worth pointing out again that a bullet’s primary cause of death is by shock, while an arrow tipped with a sharp broadhead causes massive blood loss leading to death. This distinction is important as a good shot angle for a rifle hunter is often not a good shot angle for an archer.

Shot angles, especially for archers, can spawn very heated debates. I am not here to debate, but rather to educate. The choice to take certain shots will always remain the decision of the hunter. Being educated on the different shots, as well as confident in your abilities to make certain shots, is always the responsibility of each individual hunter.

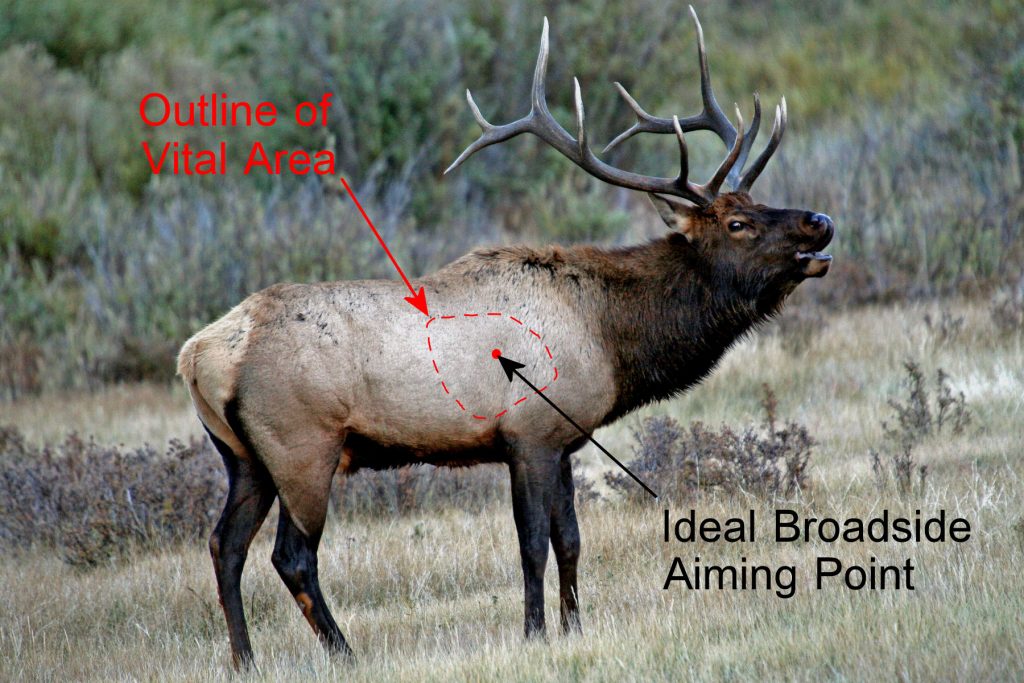

BROADSIDE SHOTS

A broadside shot is the ideal shot for an elk hunter. It provides the largest target, and therefore, the greatest margin for error. A well-placed, double-lung shot will usually provide a blood trail that is obvious and short. The ideal place to aim on a broadside shot is center of the body (vertically), and right in the “crease” that runs vertically behind the front leg. A shot in this location will put you right in the center of the lungs and provide the largest margin of error if you should miss your mark. As I mentioned previously, I’ve found that shots that hit slightly low and back, even if they clip the lungs, can lead to a longer tracking job than those that hit right in the center, or even slightly higher, in the lungs.

When I started hunting, I was taught that I needed to aim 1/3 the way up the body, right in the crease. The problem with that as an aiming point, is it removes much of the margin of error if I happen to shoot a little low or a little too far back. By aiming at the midway point between the brisket and the back – still along the crease – you now have a solid 4-6” in each direction to error and still get a solid, fatal hit.

As I mentioned previously, a shot that is too high in the thoracic cavity on a broadside shot can often result in a non-fatal wound. The infamous “dead-zone” or “void”, includes the spinous process area above the spinal cord as well as a small area below the vertebrae and above the lungs. An arrow in this region often provides a very sparse bloodtrail and typically results in a non-lethal outcome. Conversely, a very low (brisket) shot on a broadside elk can provide an incredible bloodtrail for a short distance. Shots that are too low to catch the vitals will often severe many of the veins and capillaries that feed the blood-rich muscles of the brisket. Unfortunately, as massive as the bloodtrail may be for the first 200 yards or so, it’s usually not enough to be lethal.

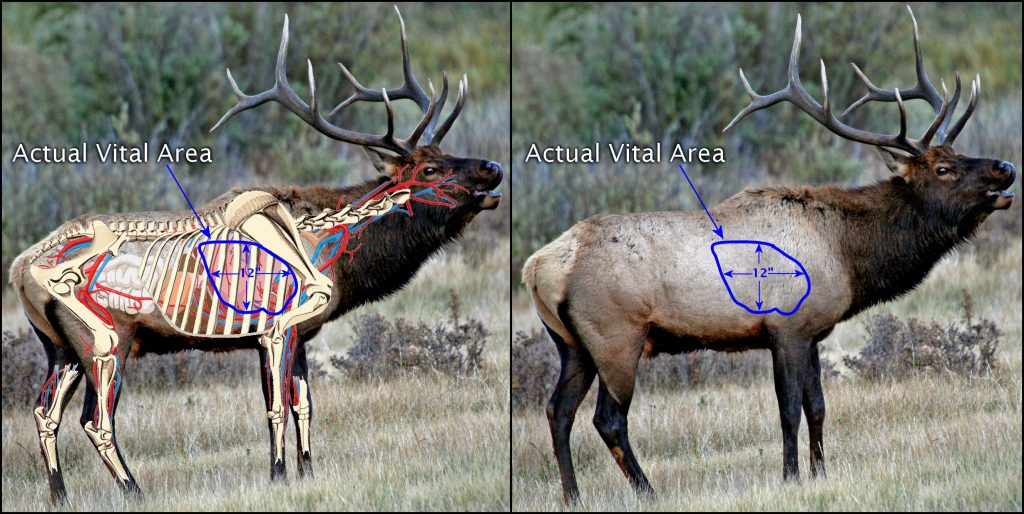

The average height of the chest cavity on a bull elk is around 24” (excluding the hide). The typical height of the vital area on an average bull elk is 12-14”. While a broadside shot provides the largest vital area to shoot at, the shot needs to be placed behind the leg/shoulder bones and in front of the diaphragm. The width of this vital area on an average-sized elk is also 12-14”. A shot in the bone structure of the front leg can be lethal for a rifle hunter, but a large amount of meat will be wasted due to the damage caused by the expanding bullet. For rifle and archery hunters alike, it is best to avoid the leg structure covering the thoracic cavity. It is also best to avoid hitting behind the diaphragm in the abdominal cavity. A shot in this area can produce a minimal bloodtrail and a long tracking job. While usually fatal, it can take several hours (or days) for an elk to succumb to a gutshot.

QUARTERING-AWAY SHOTS

As an elk turns away from the broadside perspective, the primary vital area within the thoracic cavity is still very much exposed. It is important, however, to visualize where the vitals actually sit inside the cavity, and not focus on the location of the “vital ring” that can be found on a 2D or 3D target.

As an elk shifts its perspective, the point of impact for the shot will also move. For a quartering away shot, the spot to aim for is no longer tight against the “crease”. Your aiming point will shift back closer to the diaphragm in order to keep your arrow or bullet aligned with the center of the vitals. The more the elk is angled away from you, the farther back you will need to aim.

While many hunters tout the quartering-away shot as an ideal shot, there are a few points to consider, especially for an archery hunter. First, an arrow will often hit the offside shoulder/leg bone on a quartering away shot. This means the arrow won’t likely pass-through (no exit hole), and provides only one wound for blood loss (entry hole). For a rifle hunter, a quartering away shot increases the chances of losing meat on the offside front quarter.

Additionally, if the shot enters behind the diaphragm, as is the case with most quartering-away shots, the fat that surrounds the abdominal cavity will often seal up the entry wound and produce a very limited bloodtrail.

Lastly, depending on the severity of the angle, it is possible for a quartering away shot to hit just one lung, which can greatly increase the time it takes for the elk to expire, and greatly decrease the odds of recovering that animal.

The size of the vital area doesn’t change vertically with a quartering away shot, but horizontally, the size of the target does get smaller. The sharper the angle of the elk, the narrower the target for a quartering away shot.

FRONTAL SHOTS

I won’t get into the ethical debate of a frontal shot that exists among archers, but I will simply state that there is a massive amount of blood that is circulated between an elk’s heart and brain. A well-placed frontal shot will severe multiple arteries and veins and provide a blood trail that doesn’t need to be followed. Before you decide to take a frontal shot, it is important to know the size of your target, what you are aiming for, and what obstacles stand in your way.

First, visualize where you want to aim on a broadside elk (midway up the body vertically). Then, slide that point of impact around to the front of the elk. Many people suggest aiming for the areas where the lighter brown hair transitions to the dark mane of the neck. That area is typically really close to the “bump” on the front of the elk that identifies the sternum. And that is too low, especially for an archery hunter. An arrow shot in this area has a very high chance of glancing off the sternum and sliding between the rib cage and the leg/shoulder bone, never penetrating the chest cavity.

Ideally, if you are taking a frontal shot, you will want to hit the thoracic opening. This is the unobstructed opening that leads into the thoracic cavity. An arrow that penetrates this opening will often severe the carotid arteries that supply blood to the brain as well as the jugular veins that transport that blood back to the heart. Additionally, the arrow will continue through the opening and take out the lungs. Depending on penetration, it can also take out the organs inside the abdominal cavity.

The thoracic opening begins just above the sternum, which is the point where the front ribs come together. The sternum is made up of bones and cartilage, and is not an ideal place to aim or to hit. The sternum can often be readily identified as the “lump” on the front of the elk’s chest, and represents the very bottom of the thoracic opening. From the sternum, the thoracic opening extends upward 7-8” on an average bull elk. The width of the thoracic opening is 5-6”.

I do want to point out that the vital area on a frontal shot is not limited solely to just the thoracic opening. However, if the elk is straight on and your arrow hits too far to the left or right, especially if you also hit low, the arrow will likely slide between the rib cage and the leg bone, and never enter the body cavity (see the image below). Additionally, if you hit squarely on the sternum, there is a substantial mass of bone and cartilage at that point that will prove difficult for an arrow to penetrate.

At a slightly quartering-to angle, you do gain a little on the side-to-side target, as an arrow can easily break through and penetrate the small rib bones that surround the thoracic opening. The primary obstacle on this shot is the large humerus (leg) bones on either side of the rib cage. Again, it is critical to envision where the vitals lie inside the cavity, and adjust your point of impact accordingly. A sharp quartering-to shot is heavily protected by the leg and shoulder bone, and won’t leave much of a target at all. Shooting behind the shoulder in this case will often catch only one lung and pass through one side of the abdominal cavity….neither are a high percentage shot.

This discussion of shot angles is not meant to encourage or discourage any particular shot. It is meant simply to educate elk hunters on the obstacles that need to be considered for any shot, as well as the vital targets you will be shooting for. With this education, it becomes the responsibility of each hunter to determine their level of confidence on shot opportunities, and choose to only take shots that they know will provide a high chance for a quick, clean kill.

TYPICAL BLOODTRAILS AND OUTCOMES

Having an understanding of the anatomy of the elk is a critical component of taking a shot, regardless of the weapon you are using. This understanding is also valuable after the shot as you analyze the bloodtrail and begin tracking the animal. Understanding the color and amount of blood immediately after the shot can be a great help as you determine how to proceed.

BROADSIDE SHOTS

As I mentioned, a broadside shot provides the largest target for the vitals of an elk. A broadside shot can also provide the best chance for a pass-through, which means you will often have two wounds to create a more significant bloodtrail.

Within the thoracic cavity, the most common hit will be in the lungs, and a well-placed broadside shot will almost always impact both lungs. The blood in the lungs is rich in oxygen, and is easily identifiable by its bright red/pink color and bubbly, foamy texture. A hit in the center of the lungs or slightly higher will usually result in a quick death, and a tracking job of less than 200-300 yards.

If you happen to hit the heart, the blood will be very bright red, but will not be foamy like a lung shot. However, you won’t need to track an elk that has been shot through the heart. They will fall within eyesight or earshot. If you hit the area right behind the heart, it is possible to hit below the lungs or clip just one lung. These shots often look “perfect”, but you will find minimal blood and a long trail to a questionable recovery. A shot in this area will often produce results very similar to a gut shot, which can be very confusing and frustrating when you see your arrow hit right where it is supposed to hit.

A neck shot on a broadside elk will often produce a minimal trail of dark red muscle blood. Even if an arrow remains in the neck, it will usually not be lethal. The thick hair on the neck of the elk will also absorb much of the blood, and the bloodtrail will usually be nothing more than periodic drops after the first 150 yards or so. You will likely find smears of blood on higher branches or brush, but not much for drops on the ground. Additionally, an elk shot in the neck will usually not get sick and bed down.

A low shot in the brisket (low neck or armpit) will usually produce a large amount of blood for 200-300 yards, but the trail will dry up quickly after that. You will likely find drops of blood here and there for another 100-200 yards, but most shots in this area end in frustration and are non-lethal. You will find less smears of blood with these shots, and the blood will usually be found in drops as it falls from the underside of the elk. Once in a while, the sudden loss of blood from a brisket shot will cause the elk to bed down after 200 yards or so, but if they are jumped from their bed, the blood trail is usually very minimal from that point, and it is unlikely they will bed down again.

A shot in the leg (radius or humerus bone) or the shoulder (scapula) is often audibly evident by a loud “thwack”. The arrow typically doesn’t get more than an inch or two of penetration, and the bloodtrail is typically not more than a handful of drops over the first 100 yards. These shots are not lethal for an archery hunter. There is one exception that I have seen, and that is if an arrow penetrates the thin area on the upper part of the scapula. I have seen arrows make it through the scapula and into the lungs, and that shot provides a lethal result just as a standard lung shot would.

As we transition back into the abdominal cavity (guts), the tracking job gets exponentially more difficult. On the back edge of the lungs, just on the other side of the diaphragm inside the abdominal cavity, lies the liver. The liver sits in the back part of the rib cage, and slightly above center in the abdominal cavity. A liver hit will produce minimal, yet consistent blood, and the blood will be very dark red. A liver hit will be fatal, but it will take more time – often 3-4 hours – for the elk to expire. If you find dark red liver blood, it is best to back-out and give the elk sufficient time before tracking. An elk that has been shot in the liver and not pushed will typically bed down and expire in the first 200-400 yards.

Pretty much everything else inside the abdominal cavity is stomach and intestine. A shot in this area will produce minimal drops of blood from the membrane of muscle that covers the abdominal cavity. You might also find a few drops of green stomach matter within the first 100 yards or so. An elk shot in the stomach will often begin to slobber a clear liquid from its mouth further down the trail, and I’ve successfully tracked elk on nothing more than a minimal trail of this clear liquid once the bloodtrail has ended.

A shot in the abdominal cavity is generally a lethal shot, but again, I’ve seen elk go 36 hours or more before succumbing to this shot. If you suspect an abdominal hit, it is best to back-out and give the elk several hours. They will often get sick and bed down shortly after the shot, and if they aren’t bumped inside the first 2-3 hours, it will be more difficult for them to get up and run. If you do bump a gutshot elk soon after the shot, they will often run a long way and not leave much – if any – blood to follow. I’ve seen elk with an abdominal hit go over 3 miles after being bumped. Generally though, they will bed down within 400 yards if they aren’t pushed.

Lastly, an arrow in the back leg of an elk is typically non-lethal. The one exception I mentioned previously is the severing of the femoral artery. In this case, there will be very rapid blood loss leaving a massive blood trail and a short recovery. Aside from the femoral artery, the blood trail will be rich, red drops of muscle blood, but will likely diminish very quickly. An elk shot in the back leg will usually not bed down, and the blood trail will likely be insignificant after 200 yards or so.

QUARTERING-AWAY SHOTS

The general explanations of typical bloodtrails from broadside shots begins to blend as we transition into quartering away shots. Often times, a quartering away shot will not produce a pass-through for archers, meaning there will only be one hole for blood to escape from.

Additionally, in order to place the broadhead of the arrow in the center of the thoracic cavity, the entry hole will typically be back in the abdominal cavity. The fat surrounding the organs in the abdominal cavity can act as a “plug” on the entry hole and prevent blood from escaping. As such, quartering away shots – while fatal – often result in very minimal bloodtrails.

Depending on the angle of the quartering away shot, it is possible to hit both lungs. Similar to a double-lung shot on a broadside elk, the elk usually don’t go far and the bloodtrail is easily identifiable. Quartering away shots often lead to a single-lung hit though, due to the angle at which the arrow hits the body cavity. While a single-lung hit is a lethal shot, elk can survive with one lung for extended periods of time, and can travel a significant distance, especially if bumped. If you suspect that you might have only caught one lung, it is best to give the elk more time before taking up the trail.

FRONTAL SHOTS

Due to the proximity of so many main arteries and veins in the thoracic opening of an elk, there are few blood trails as devastating as those from a well-executed frontal shot. As impressive as the blood trail from a frontal shot is, I have very rarely ever needed to follow one as the elk usually falls within sight.

Watch the effectiveness of a well-placed frontal shot on a bull elk in the video below:

I have witnessed frontal shots not go according to plan, though, as well. There are two main obstacles that prevent frontal shots from working out; hitting too far to the side (left or right), or hitting too low. If an arrow hits too far to the side, it can deflect off a rib and slide between the front shoulder and the rib cage. I have seen full pass-through arrows that entered the front of the elk and exited behind the front shoulder without penetrating the body cavity or hitting anything vital. This shot will produce a limited amount of red muscle blood. If the arrow hits even more toward the outside, it will contact the humerus bone and get very little penetration. This will also result in a non-lethal hit, with minimal blood.

A frontal shot that hits too low will generally produce a lot of blood over the first 200-300 yards. This is due to all the blood vessels that run through the muscles of the brisket. Penetration is typically not great if you hit directly on the sternum, but it can slide along the rib cage and get good penetration if you hit slightly to the side or below the center of the sternum. The blood trail will often raise your excitement level, and you will swear there is no way an elk will live with that much blood loss. However, the trail usually dries up after 200-300 yards and the hit is typically not lethal as the arrow doesn’t make it inside the chest cavity.

With this extensive and detailed look at the anatomy of an elk and the possible outcomes for multiple shots and shot angles, we can now jump in and start discussing the basic strategy for tracking and following a bloodtrail.

Click ‘Next Chapter’ Below to Continue on to Chapter 2: The Tracking Strategy